The 'despotic' power of government: when the state takes what's yours

A national litigator weighs in on local eminent domain case

RICHMOND — Scott Gabbard will have his day in court next month to argue that the state’s offer for the right of way to build a road through his cattle operation, is insufficient.

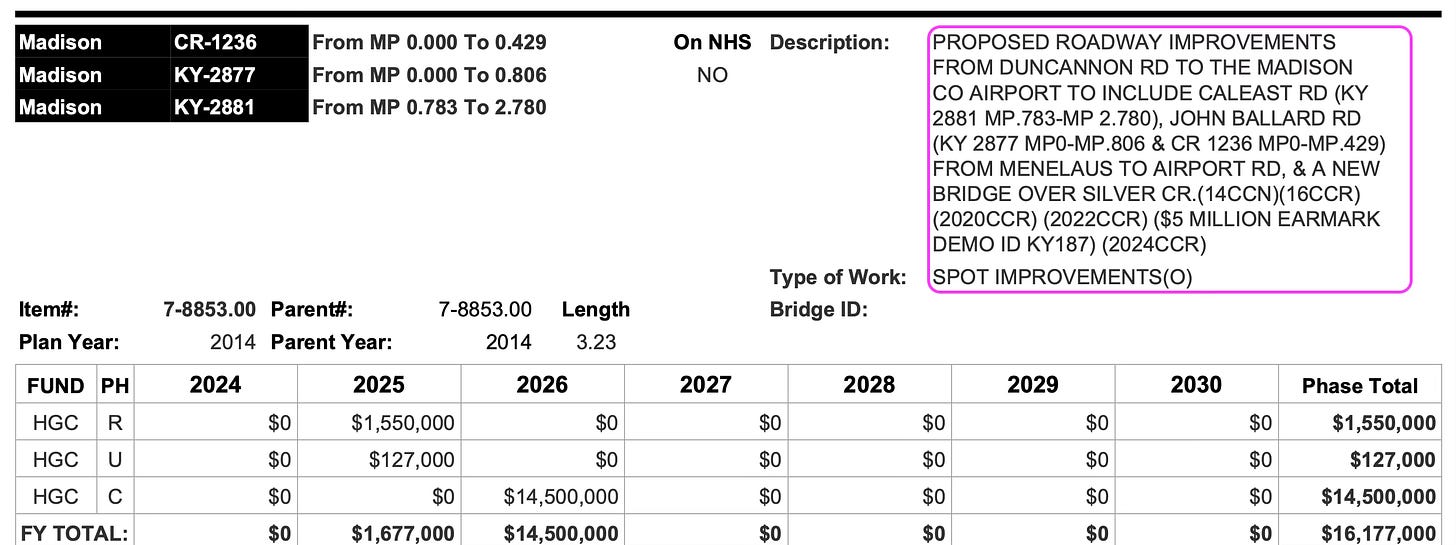

Gabbard has been farming his 148 acres off of John Ballard Road in Richmond since 2012. In 2022, he was informed of the state’s plans to build a road from Madison Airport Road to Duncannon/Peytontown Road straight through his property.

Since then, he has waged a fight to protect his land and his livelihood from eminent domain, but has been baffled by the multiple claims from county and other officials that they are not to blame, without ever sharing with him who might be.

“In our experience, it’s not unusual for property owners to be among the last to know that their property is in the cross hairs,” said Robert McNamara, deputy litigation director for The Institute for Justice, a nonprofit public interest law firm in the Washington, DC area. The Institute argued the landmark eminent domain case, Kelo v. New London, before the Supreme Court.

“Particularly with a state’s department of transportation, it can be difficult to figure out exactly who decided on this route as opposed to that route. And then the decision happens in a black box,” McNamara told The Edge in a phone interview.

What is not as frequent, according to McNamara, is that powerful people are harmed by these kinds of decisions.

From no problem to big problem

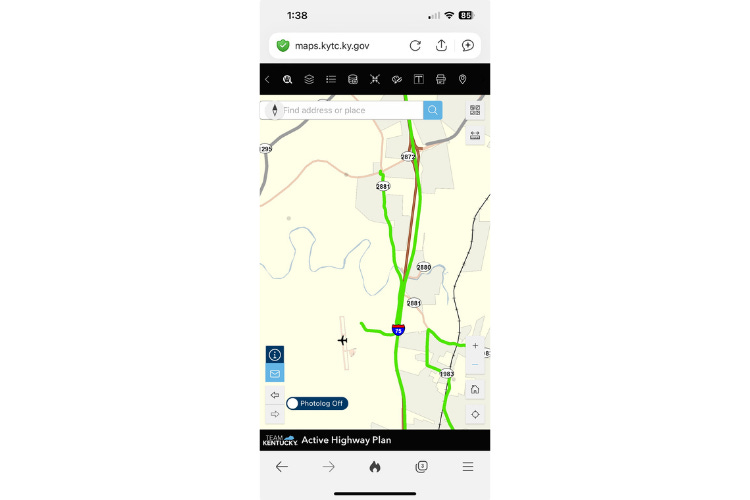

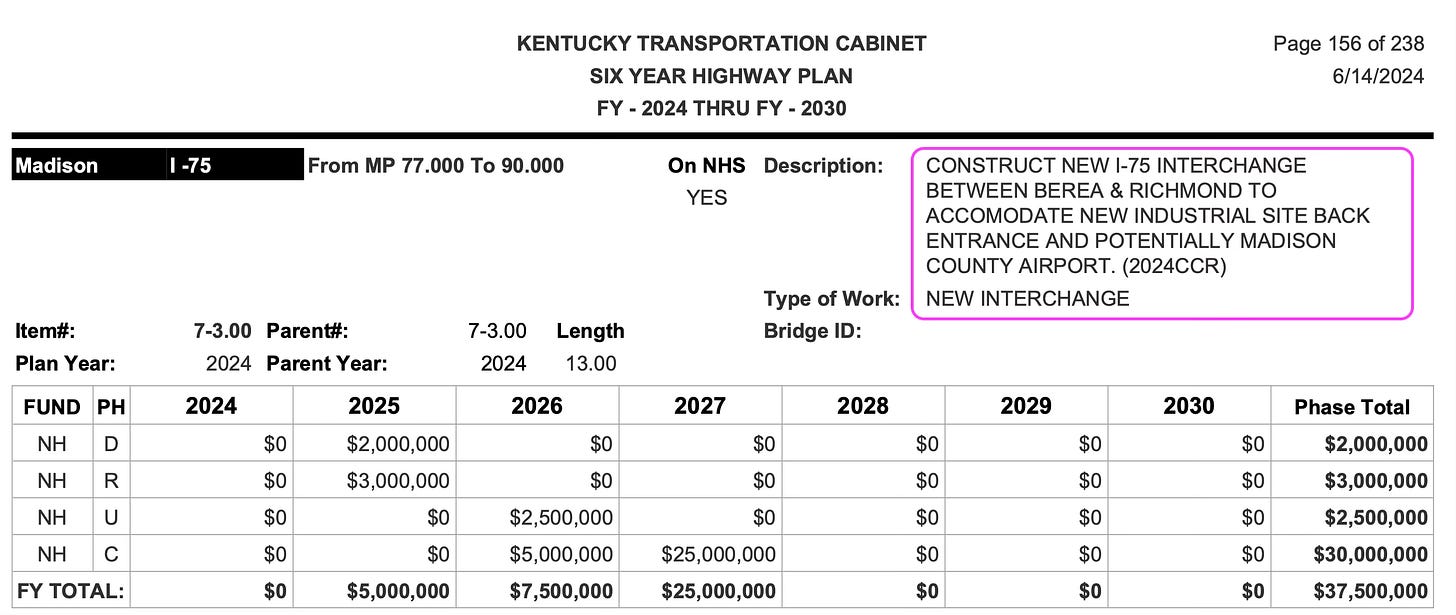

The original 2021 map of the project shows not only Caleast Road/2881 as the target of improvement, but also the option of building a connector road from the airport (see the plane icon on the map) out to I-75, by way of a new exit that KYTC also plans to build there.

But a year later, around the time the state was ready to meet with the public about the route, it claimed in a brochure distributed to affected area citizens that there needed to be a “feasible, efficient, and safe” route between the Central Kentucky Regional Airport and Duncannon Lane. KYTC listed multiple reasons why Caleast Road/2881 should not be considered for the route, calling it “narrow, rural … with little to no shoulder and inadequate sight distance in spots.”

The brochure cites a traffic analysis of the previous five years of traffic accidents and finds there had been, “24 reported collisions resulting in 1 fatality, 5 injuries, and 20 ‘property damage only’ incidents.”

Whether the traffic study was authorized before or after other routes were designated is unclear. Multiple attempts to clarify it with the KYTC were unsuccessful.

Other route perhaps disqualified

During the public meeting about the project in December of 2022, the number of potential options KYTC presented to citizens as potential routes was four, as previously reported. KYTC surveyed attendees of the meeting to see which of four options they preferred.

The survey data is not publicly available, and The Edge’s attempt to obtain it failed. However, a KYTC engineer speaking on background only, told a reporter that where a new road should be built is ultimately up to the project engineers, not the citizens. He did not confirm or deny that was the case in this project.

Further, he said the decision-making process is conducted according to federal environmental impact guidelines laid out in the 1970 National Environmental Policy Act. It calls for an assessment of how new construction might adversely impact the surroundings.

Meanwhile, an alternative to the route through Gabbard’s farm, listed on the survey included one to the east of Silver Creek where it separates Gabbard’s farm with another. A source told The Edge that during a site inspection, indigenous artifacts were discovered, making that route less desirable. The Edge was unable to confirm this officially with KYTC, but the KYTC source speaking on background did say that the engineers do try not to disturb archaeological finds.

Boon for developers

Gabbard believes Caleast/2881 could be widened and improved well enough that the state’s original plan for connecting the airport to Duncannon Lane would work, especially if the airport will be connected to I-75 with a new road and exit. He also thinks the route through his farm holds special appeal to developers, and that is why the state switched routes.

After the road to Duncannon Lane is completed, London, Ky.-based developer, Begley Properties, will own the properties at three corners of the intersection. Begley has been buying up much of the available land on Duncannon Lane over the past several years. Gabbard said having a new road there will make development more lucrative for them.

While no official would confirm this to The Edge, the state generally affirms this in its brochure. “A 2017 small urban area study shows a significant increase in anticipated traffic due to investments in the airport and potential commercial and multi-use development in the area,” it reads.

McNamara said if Gabbard can prove his theory of developers benefitting from the state’s right of way through Gabbard’s farm, there is a chance he could be paid more.

“Once that road is built, and then the acreage around it goes up in value—that’s a common eminent domain fight. It’s called ‘project value’. If the consequence of the road is that property values go up, then you’ve got an argument. It’s, ‘Why am I the only one who doesn’t get to benefit just because I’m the one you’ve taken land from to build the road?’”

The role of ADDs

In Kentucky, the Council of Area Development Districts, created by state executive order in 1967, have significant lobbying power to sway state legislators toward funding highway projects that lead to economic development in the District’s home region. They typically are the body to negotiate between local and state leaders, according to their website.

In a sideline interview at a Madison County Fiscal Court regularly scheduled meeting, The Edge spoke with David Duttlinger, executive director of the Bluegrass Area Development District, which includes Madison County, to learn about what influence his ADD might have had on this road project. His answer was, he didn’t know. It was before his time, but he said it would have made sense that there had been collaboration between his ADD and the state about the road project.

Duttlinger’s District is involved in this project now, but only tangentially. He said in the interview that his ADD helped ensure that the airport would receive a loan from the Kentucky Infrastructure Authority of about 1.8 million dollars with the City of Berea acting as the pass-through agent. Berea Mayor Bruce Fraley agreed to present the idea to Berea’s City Council, which passed it unanimously.

Whether or not the public approves of what the Council of ADDs do is mostly immaterial. Members of the respective ADDs are unelected policy advisors, typically appointed by their local officials.

“ADDs do a great service to our communities” Fraley told The Edge in a phone interview, and said he had not known about the road going through Gabbard’s farm. “I would not want a road going through my farm, but I respect the process,” he said.

The ‘despotic’ power of government

If the ADDs “might” have been involved, but its leadership doesn’t know for sure, and local officials deny they are involved, then who?

The Edge attempted multiple times to reach the office of Gabbard’s State Representative Deanna Frazier Gordon (R.-Dist. 6) for comment on why she thinks this might be a good idea. Her public information officer said Gordon declined to comment because the case was being litigated.

“I’ve yet to see an eminent domain case that has a gag order,” said McNamara.

The fact is, Gabbard may never know who ultimately is behind the decision to take a portion of his farm, according to McNamara.

“Eminent domain historically has been referred to as the despotic power of government,” he said. “It is the overwhelming force of government to take by force what is in any other circumstance, undeniably yours to own.”

Part and parcel to this despotism, according to McNamara is to disrespect the person whose property is being taken.

“Eminent domain takes away the obligation to treat the property owner as a human being, and so often it leaves people with feelings of just utter powerlessness. Having your land forcibly taken away is radicalizing.”

This story was updated to include Kelo v. New London.

I was appointed to the ADD Board representing the county when I was Madison Co Solid Waste Coordinator. We had minutes taken by staff and they were voted on each time we met. There should be an archive somewhere-maybe even in the clerk's Fiscal Ct records? What has disappointed me for years since moving back in 1979 was the constant development of good productive farm land for housing. It seems so very stupid to me. The results of the survey being unavailable adds distrust of government officials and their actions.