Remembrance: Jack Marema, 1928-2024

My dad was reliable to a fault, but his life did not follow an entirely predictable path. You might call it the knuckleball effect. He called it something else.

My dad was an exceptionally reliable man, which made his knuckleball all the more surprising.

It was hard to believe that a man so dependable could throw a pitch as unpredictable as a knuckleball. But he could, and often did, in our nightly games of catch when I was growing up in rural Jackson County, Kentucky.

I could tell when a knuckler was coming because of the mischievous look on his face. But knowing a knuckleball is coming does not mean you know where it’s going. The erratic nature of a knuckleball would make me giggle as I tried to catch it.

I once misjudged a throw so badly that I stopped the ball with my nose. Dad used a garden hose to clean me up. I had to beg him to put the knuckleball back into the rotation, which he finally did.

I’ve been thinking a lot about my dad, Jack Marema, in the last few weeks. He died in December at the age of 96. On February 1, 2025, we will celebrate his life in a service in Holland, Michigan, where he lived at the time of his death.

On the surface, Dad had a quiet and steady life. He died about 30 miles from where he was born. Aside from a two-year hitch in the Army and summer jobs in a refrigerator factory, he worked in the field of education his whole life. He and my mom were married for 65 years, until her death in 2016.

Dad mowed the lawn once a week. He used a full Windsor knot in his tie as if he didn’t trust a half Windsor to do the job. He ate the same thing for breakfast and lunch most days. He watched Walter Cronkite at 6:30 and “Wheel of Fortune” at 7. He kept up with oil changes and tire rotations. He counted the offering at church.

And yet, there was what we might call the knuckleball effect – unexpected shifts and changes that altered the course of his life profoundly. He was reliable to a fault, but not always predictable to someone who wasn’t paying attention.

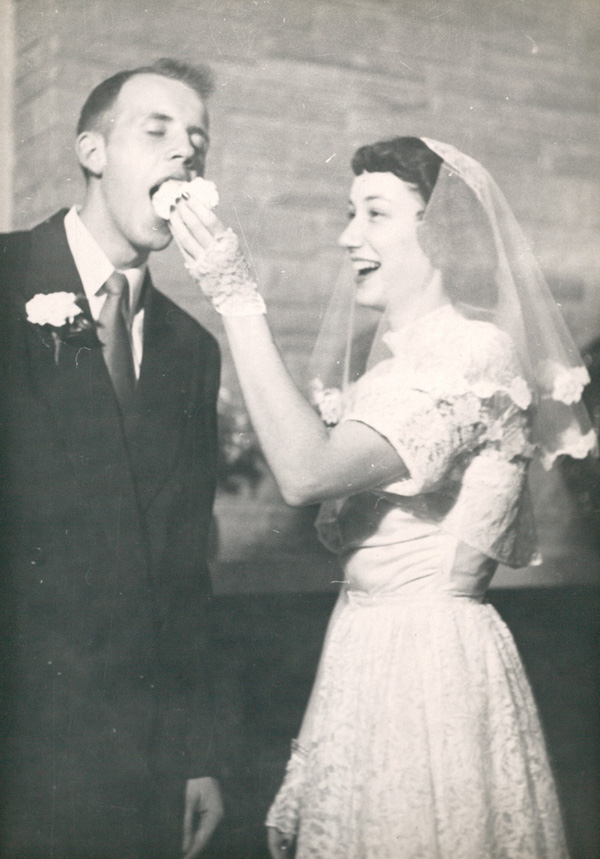

First, there was my mom.

Dad was raised in the Dutch American stronghold of Grand Rapids, Michigan. He got a strict upbringing in the Reformed faith of Dutch immigrants. The Reformed denominations are a lot like Presbyterians, except Jesus spoke Dutch before learning King James English.

Dad attended Hope College, which was affiliated with the Reformed Church. The chance that your classmate at Hope was also Dutch and Reformed was high in the late 1940s. But my mom, Nancylee Corp, was neither. Mom was a music major from Auburn, New York. She was English American and Episcopalian.

Initially, my dad’s parents weren’t thrilled with Dad’s choice of a girlfriend.

“Jack, she’s not Reformed and she’s not Dutch,” my grandpa said, according to my dad. “If we had wanted that, we could have sent you to a state school.”

Dad never told us this story until years after my mom died in 2016. I doubt he ever told my mom.

Dad was not a disobedient son. But on this matter of the heart, he wisely bucked convention.

Eventually, Mom won over her in-laws. It didn’t hurt that she remained in Michigan, “converted” from her Episcopalianism, played the organ and directed the choir in a Reformed Church, and gave birth to three grandchildren, all of whom were promptly baptized into the faith.

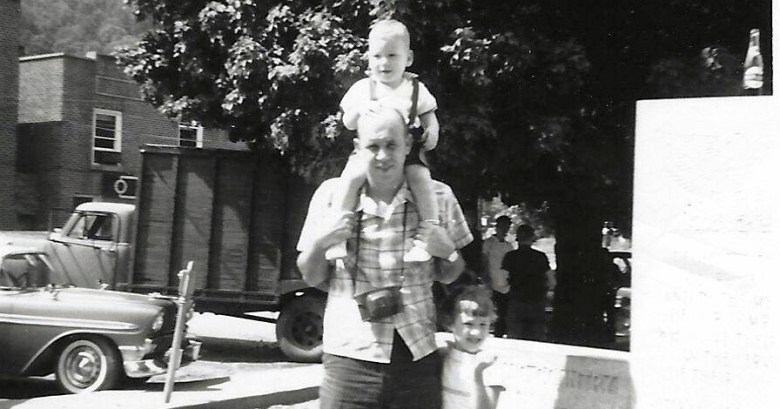

The next manifestation of the knuckleball effect was geographic. After Dad’s military service, Mom and Dad settled in the small town of Galesburg, Michigan, which is about an hour south of Grand Rapids. With three kids, steady teaching jobs, and family nearby, the path of their lives seemed set.

But in college, Dad had learned about Annville Institute, a settlement school run by the Reformed Church in America in Eastern Kentucky. The school opened in 1909 to serve Jackson County and the surrounding Appalachian region when educational opportunities there were limited. Mom and Dad liked the idea of going someplace where they might be able to make a bigger difference for the young people they were teaching.

Annville was small and remote in the early 1960s. The moving company couldn’t find it on any of their maps. “Lady,” the dispatcher said to my mom when she called to get a quote, “are you sure you want to move there?”

She did, and that’s what happened. We left Michigan when I was a couple months old. My sisters were 3 and 7.

My earliest memories are of Eastern Kentucky, growing up in a culture and economy very different from what we would have experienced in West Michigan. At Annville I was around a lot of families from the North. But I also made friends with people whose families had lived in the county for generations. Over time, all of us in the Marema household saw something special about our new home, and it changed who we were. My understanding of rural America and my work at the Daily Yonder and Center for Rural Strategies go back to my earliest days in Eastern Kentucky.

When the time came for Mom and Dad to leave Annville in 1974, Dad again did something unexpected. Instead of returning to Michigan and picking up his teaching career there, my parents decided to remain in Kentucky.

As Dad told the story, one afternoon he drove over to Berea College, about an hour from Annville, just to look around and see if he could learn something about working there. He liked the small, liberal-arts college because it served Appalachian young people who might not otherwise be able to afford college.

Without an appointment, he dropped by the office of the college president, Willis D. Weatherford Jr. “I thought I might as well start with the head guy,” Dad told me years later.

Dr. Weatherford took time to hear Dad’s story. He made two calls and sent Dad to speak with other staff. A couple months later, we moved to Berea. My dad worked in the college’s financial aid office for the next 20 years. My mother also worked for the college and as a music teacher at Berea Community School.

Berea, at about 7,000 residents in 1974, was shockingly large compared to Annville. But the change, as dramatic as it was, was nothing compared to what I would have experienced if we had moved back to West Michigan – a place I had only visited and never considered home. I know my parents considered my preferences in their decisions, and I’m grateful. Because spending the second half of my childhood in Berea, with the college’s focus on Appalachian culture and social issues, was another big factor in shaping my life and work.

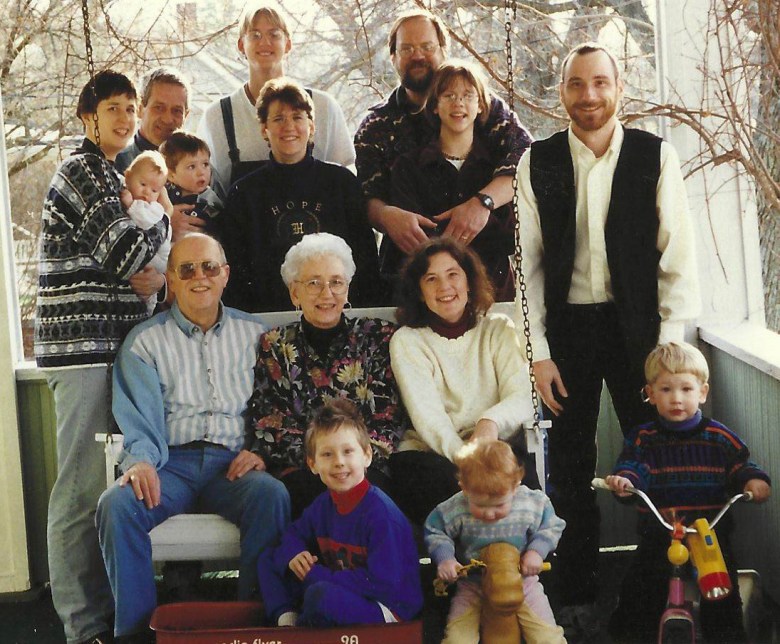

In 2010, after 48 years in Kentucky, my parents moved back to Michigan. I always knew they would abandon me south of the Ohio River. It just took a lot longer than I thought it would. Mom and Dad were very settled in Berea, but the city had no good options for senior living, and they figured if they had to move, they’d rather go to Holland, Michigan, where my sister lived, than a city like Richmond or Lexington, where they had no family.

It was another unexpected choice, and another good one. In Holland, Dad’s life came full circle, back to the denomination he was raised in, back to good friends from college days, and back to many of the families they had worked with at Annville.

And, best of all, they were close to my sister, who had lived in Holland since going to Hope College in the early 1970s. She and her friends and family welcomed my parents into the fold and encircled them with love and support in the later years of their lives.

So there it is – the twists and turns of a single life, enmeshed with so many others, including mine. Ultimately, the knuckleball landed with a thwack in the catcher’s glove.

Dad would not have referred to his life’s unconventional choices as the knuckleball effect – random and uncertain. His way of making big decisions – whom to marry, where to live, what to do – relied on careful intuition, guided by his faith. He occasionally spoke of “being led” to do something, but never with bravado or certainty. He described it more as a quiet insight, a careful testing of the waters, a patient waiting for something to be revealed. And then the next step, careful if not entirely expected.

And from time to time, I would see the slightly mischievous look on his face, the kind that made me giggle with anticipation when I was a kid. As if he was saying, “Get ready, here comes a surprise. And even if you aren’t quite sure how things will turn out, it’s going to be worth it.”

And he was right.

Tim Marema is the editor of the Daily Yonder. He lives in Norris, Tennessee. He and his wife, Liz McGeachy, have two adult children.

This article first appeared on The Daily Yonder, and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

The Edge is Berea’s source for reliable news, in-depth journalism, and thoughtful commentary.