'Poor communication is an EKPC strategy'

Lack of clarity about the utility's aims irks opponents of the Big Hill Line

SOUTHERN MADISON COUNTY—Five property owners in Big Hill, Pilot Knob and Red Lick, plus a few more just over the border with Jackson County, were among the last to know the details of a plan to build a nearly nine mile long transmission line through their respective properties.

Eastern Kentucky Power Cooperative’s first public announcement that it would construct the 69 kilovolt Big Hill-Three Links line (aka, the Big Hill Line), and a substation on Red Lick Road, came in the form of a legally mandated letter, sent in September 2023, to area residents determined by the co-op to be most impacted by the development.

The letter told of a meeting to be held a couple of weeks later at Berea College’s Forestry Outreach Center where all would be explained.

The letter did not reach all relevant addresses, instead arriving at several homes which were not in the direct path of the transmission line. But word spread quickly among neighbors, and on the night of the meeting, the room was filled to overflowing with people who wanted answers to their many questions.

Questions such as, why had no one in the neighborhood been consulted about the plan for the powerline before it was determined? What did this mean for property values? What about the view from the Pinnacles? What might be the impact on the watershed for Owsley Fork reservoir, the primary water source for much of the county and all of Berea? Would the line adversely impact tourism in an area popular with outdoor enthusiasts?

Area resident, Nicole Garneau, recalled the scene in an interview with The Edge. “We all came with our questions, but it wasn’t a real meeting. EKPC had little stations where it was one of their people to one of ours. It was divide and conquer. It’s not like there were chairs arranged so we could sit together and listen to someone talk to everyone all at once and answer our questions so everyone could hear the answer.”

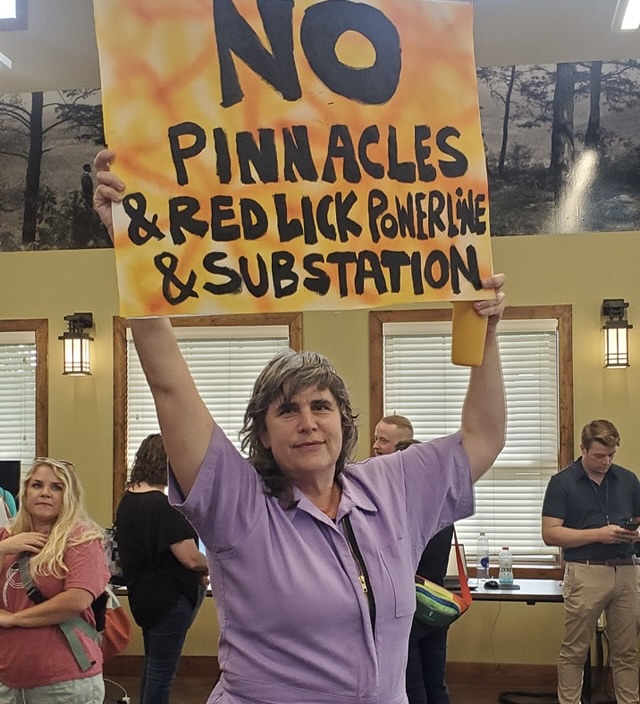

Clear Creek resident, Nicole Garneau, carrying signs in protest of the Big Hill Line. Photos courtesy of Nicole Garneau

Garneau, who lives in Clear Creek, does not own property directly impacted by the line, but says she enjoys spending time in the wooded landscape that surrounds the reservoir, and the Pinnacles.

She began walking around the room where the meeting was being held, waving protest signs she and others had made in advance of the meeting. Then she grabbed a microphone and demanded the representatives from the power co-op face the crowd.

That night at the Forestry Outreach Center marks the beginning of a now two-years long struggle to demand the power cooperative listen to its member constituents and be transparent about its movements to build the line.

Their success, however, has been minimal according to some.

“One thing the Big Hill Line exemplifies is the inability of the people to be able to actually participate in the government,” activist and Berean, Bugz Fraugg, told The Edge in a text. “People were willing to come together to understand the project and to negotiate. EKPC has been unwilling to have frank conversations with concerned constituents that will be impacted by the Big Hill Line, whether or not they are land owners. Poor communication seems to be their strategy.”

Amber Falle and her husband, Marty, Jackson County property owners who are being sued by EKPC in an eminent domain case, are among those who believe the power cooperative deliberately avoids communicating clearly about its intentions.

“We never got that letter they supposedly sent out in September,” Amber told The Edge in an interview. “We didn’t get a letter until February 2024,” she said.

Robert McNamara, deputy litigation director for The Institute for Justice, a nonprofit public interest law firm in the Washington, DC area, told The Edge in an interview that property owners potentially impacted by eminent domain are typically given very as little information as possible by the entity doing the taking. “They are likely the last to know about plans that might involve condemnation,” he said. Condemnation is the technical term for when land is taken for public use.

Increased demand for power

EKPC, along with other power utilities across the state, are under pressure to improve and expand Kentucky’s aging power grid, particularly as demand for energy increases to support the Beshear administration’s bid for rapid high-tech industrial growth across the Commonwealth.

Federal statistics show that Kentucky is already one of the nation’s most energy-intensive economies, ranking among the top 10 states for amount of energy used per dollar of gross domestic product.

Industry is the state’s largest energy consumer, accounting for more than a third of all end-use energy consumption statewide. Add in the state’s new electric vehicle battery factories, plus the increasing number of data centers and that usage is predicted by EKPC’s regional transmission organization to soar.

EKPC is part of the regional grid known as the PJM, so-named for its original founding states, Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Maryland. The PJM now includes Kentucky and several other states, and the District of Columbia.

The PJM long range forecast released earlier this year, is for summer peak energy demand in the region to more than triple in the next 15 years, from 70,000 megawatts, to 220,000 megawatts. The PJM notes in its report that current energy usage projections equal the fastest rising demand for power since 2006, and specifies data centers and EV battery manufacturing as key to this trend.

“EKPC is taking steps to prevent outages from happening,” EKPC spokesperson, Nick Comer, told The Edge in an email. “During extreme cold weather in January 2025, high electricity usage caused substation equipment [serving the southern end of the county] to operate near its capacity, threatening overload, which could cause power outages for homes and businesses.”

Comer said that the majority of the power cooperative members in the southeastern part of the Madison County are served by a substation that currently serves 4,100 meters, “more than any other substation in EKPC’s system”.

Once the Big Hill Line is completed, only about 1,500 meters will be connected to the substation on Red Lick Road, he said. “This will provide more flexibility to serve these homes with electricity from either the south or the north, reducing the risk of outages,” Comer said.

Questions about line remain

The power co-op claims it has accommodated local residents impacted by the line. “EKPC has listened and responded to the concerns of the community and affected property owners about potential impacts of this project,” Comer wrote in the email. “EKPC is taking reasonable steps to mitigate impacts while ensuring reliable electric service.”

Opponents disagree.

When the power co-op sued Berea College earlier this summer to condemn about a mile of the forest to build a portion of the transmission line, the College responded by demanding answers to multiple questions about how and why EKPC planned to build the line, and what other alternatives exist. Questions, the College said in a statement, it has been asking the power utility to answer since the outset in 2023.

The College’s response to EKPC’s complaint, filed with the Madison County Circuit Court, also demanded a slew of documents the College said EKPC had previously been unwilling to produce, including proof of an environmental impact study.

The utility has until September 15 to respond, but has since issued a public statement indicating it has conducted a federally stipulated environmental study, saying the study has been, “reviewed and approved by the Rural Utilities Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.” The statement also reiterated that the power co-op, “has listened and responded to the concerns of the community and affected property owners about potential impacts of this project.”

Previous attempts by the Kentucky Resource Council to receive evidence of an environmental impact study also went unanswered in the past.

Potential environmental impacts

The Edge requested a copy of the impact report from EKPC but did not receive it. A letter from the Department of the Interior’s fish and wildlife division’s Kentucky field office, however, indicates it assessed the area to be impacted by the line and that while several species of bats possibly may be imperiled—the Indiana bat in particular, is likely to be adversely impacted—other damage would be minimal. EKPC has not publicly addressed the matter of the potential fate of the Indiana bats.

In the statement, EKPC did however, address concerns about the line marring the viewshed from the Pinnacles, saying the line would be screened largely (but not entirely) by Pilot Knob. In the statement, the utility dodged concerns in its statement about how the line might impinge on the bucolic feel of Windswept, the College’s retreat and conference center overlooking Owsley Fork reservoir, also home to an observatory. The College demanded an answer in its response to EKPC’s suit.

The City of Berea had contracted an engineering firm to assess the line’s potential impact on the water quality of the reservoir, the source for the City’s water. The engineering report concluded the line, “would not result in a significant enough impact on water quality.” Therefore, EKPC pledged in its statement to follow the firm’s best practices for vegetation management around the transmission lines.

“EKPC is continuing right-of-way acquisition and plans to commence clearing and construction in 2026,” Comer said.

There is more to come on this story. Please subscribe and watch for additional coverage of the impacts of eminent domain, industrial expansion, and other land use issues, here at The Edge.

Investigative reports like this one need funding to produce, even if they are gratifying to report. The Edge NEEDS your support if it is to continue bringing you quality, reliable, local journalism. Please subscribe today. Thank you!