Dysfunctional leadership at heart of Berea Independent budget woes

Part One: Lack of oversight leads to bloated staffing levels

BEREA — Lack of oversight and poor communication on the part of Berea Independent Schools leadership helped create the District’s nearly 2 million dollar deficit, leading to mass lay-offs and the administrative leave of the superintendent, The Edge can report.

Speculation in the community about why the District is in dire financial straits has run the gamut from it being down to the spending habits of the former superintendent, Diane Hatchett, PhD, to the cost of consultants, to a failed solar panel project.

After reviewing multiple documents, and speaking with — in some cases, multiple times per source — over a dozen current and former school administrators, board of education members, teachers, and others — most of whom spoke freely but did not wish to speak on the record — the composite picture renders those theories as symptoms of a larger problem.

At the heart of the matter was dysfunctional leadership, marked by a lack of communication and a high attrition rate that disrupted the continuity of academic initiatives, all of which suffered from lax oversight by the District’s board of education.

In this first of several investigative reports into the District’s crisis, The Edge examines how inattention to staffing levels slammed the administration into a figurative brick wall.

Lack of oversight created crisis

Audit uncovers trouble

At the end of last year, Tom Sparks, auditor from Summer, McCrary & Sparks PSC, in Lexington, found something troubling during a routine audit of the Berea Independent District’s books. Namely, a 1.7 million dollar deficit with no revenues in site to turn the red to black. Sparks advised the District’s Board of Education during its regular December meeting that if it didn’t figure out a solution, “The state will be proactive in your management of the District.”

The solution was to cut staff. The task fell to the superintendent.

In March, during the Board of Education’s regularly scheduled meeting for that month, then superintendent Diane Hatchett, PhD, officially informed the board she had laid off three-dozen staff. This was expected to save 1.3 million dollars, she said. Hatchett detailed her budget strategy in a Powerpoint presentation, saying that the Kentucky Department of Education was on board with her plan and would in essence, watch and wait to see what happened next.

Parents were outraged by the news, and by the way the firings had been handled with teachers having to walk alone across the parking lot, be fired, and return to teach the rest of the day.

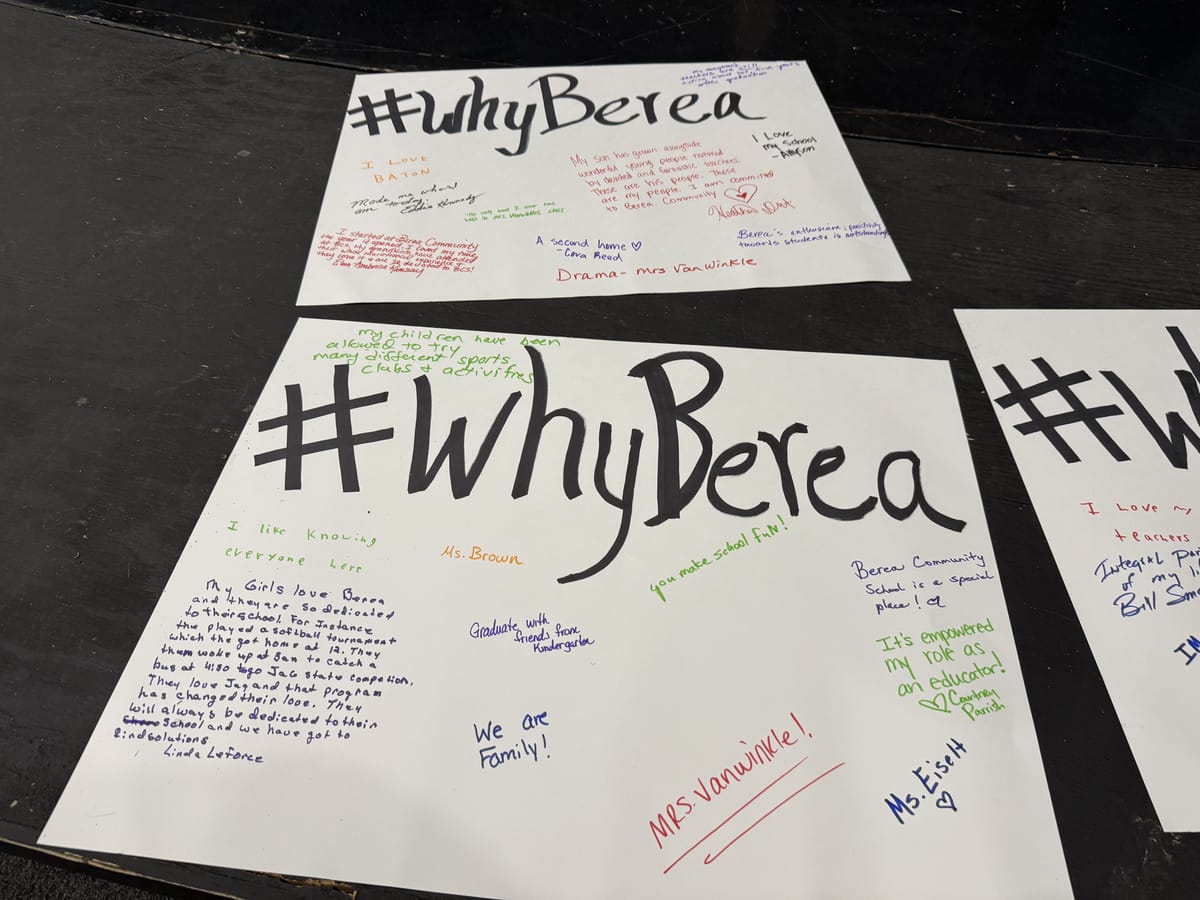

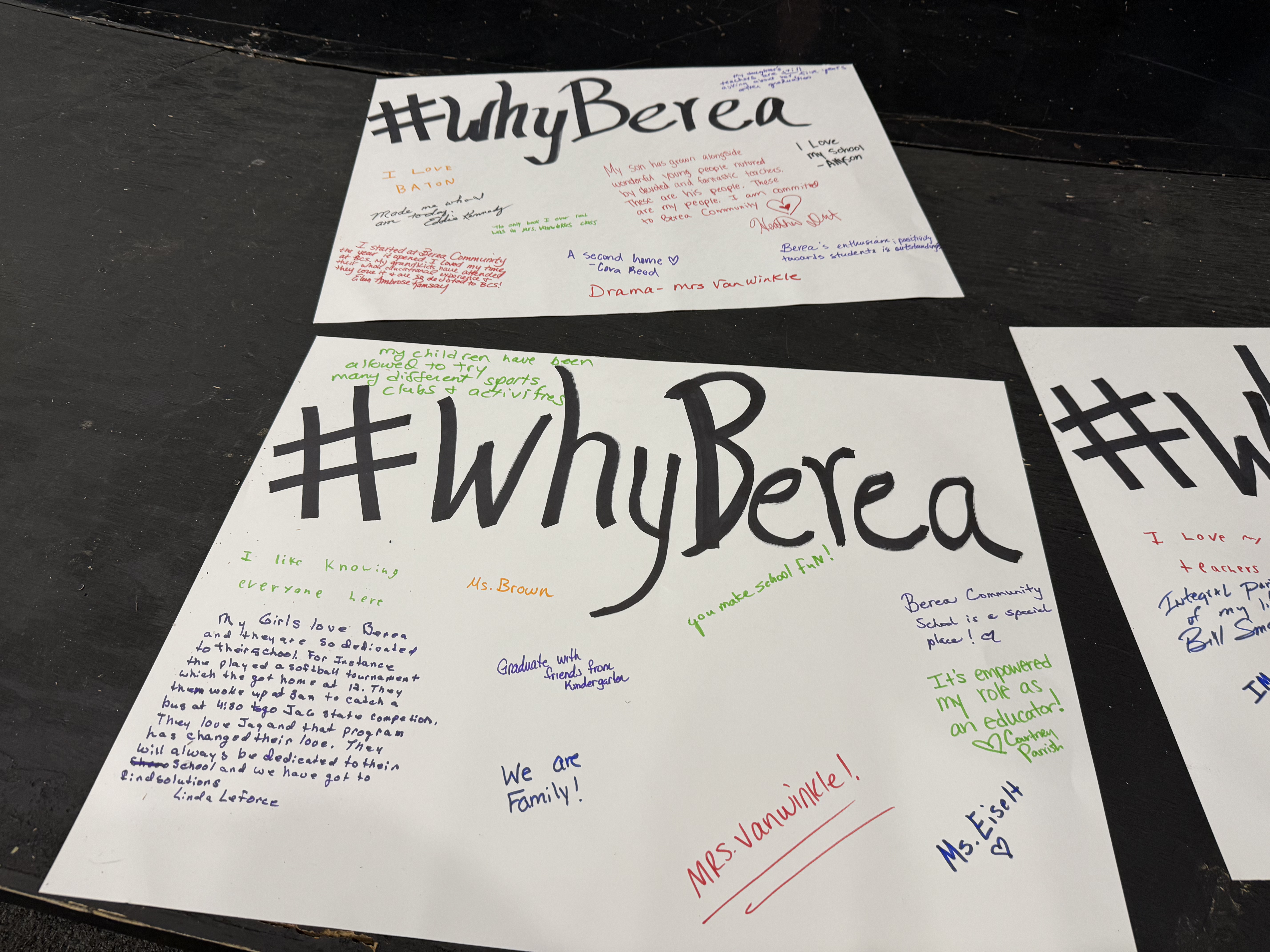

Teachers and parents came to the mic during the public comments section of the meeting, and excoriated Hatchett, who was compelled to sit and listen as one after another speaker spoke shared their pointed thoughts about her leadership, her spending, her thoughtlessness.

For more coverage of this story, including of the Board of Education meeting where parents spoke out, visit this story. You can also visit The Edge’s archive and search “Berea Independent”

Things moved quickly after that.

By month’s end, at a special called meeting, Board Chair “J” Morgan announced that community outrage necessitated the Board’s unanimous decision to launch an investigation into the budget shortfall and also the placement of Hatchett on administrative leave.

In the interim, Morgan announced that Thomas, a former Madison County Schools superintendent who has made a second career of being interim superintendent for troubled districts, would both lead the District and the investigation.

All Board members but Jackie Burnside, PhD, agreed to Thomas’s appointment. Burnside abstained, citing her concerns over Thomas’s $568 fee per day, or nearly $37,488 for the three months of his contract.

Too many teachers

Despite community upset, even if there had been more revenues, the truth was that there were indeed too many teachers. That’s according to Nathan Sweet, finance officer for the District, who explained to The Edge that for some time, District leadership had neglected to conduct annual reviews to see which teaching positions funded by monies other than state funds were expiring and should be eliminated.

When Sweet did look over all staffing, he discovered a mess.

“With positions not listed on the allocations and no centralized list there was not a good system for making sure that when an allocation was reduced or a grant ended that appropriate cuts were made,” Sweet wrote in an email.

Before each school year, the state department of education reviews enrollment levels to determine how many teachers the state should fund in each district. Additional staff outside of state allocations can be supplemented by other funds such as state and federal grants, or Title 1 monies and so on, according to Sweet.

“The schools were given their numbers but there was not a check happening in the background to make sure they were actually staffing at those numbers,” he wrote. “Many of the positions that are being eliminated would never be reflected on an allocation because they are either classified or report to a supervisor other than a school principal.”

The interim superintendent agrees.

“In ‘23-’24, we had 12 million dollars of revenue and the money spent on staffing was 11.3 million dollars,” Thomas told The Edge in a sit-down interview. “My point is that there was not much left over for operating expenses. I don’t think we ever should have gotten to that margin.”

He likened school district governance in general to a “three-legged stool”.

“One of those legs is the superintendent. One of those legs is the chief finance officer, and the other leg would be the Board of Education,” Thomas said. “If you’ve got one weak leg on that stool, you can still probably sit on it. When you get two weak legs, you have to be very careful, but you still probably can’t sit on it. And if the third leg doesn’t have all the information it needs to be strong enough, it’s impossible to sit on that.”

Missing information

That missing information that would have covered the portion of the budget gap not created by the accretion of unfunded staff positions was news from the state that a stream of pandemic-era funding was ending.

ESSER monies (Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief) were federal funds distributed to all Kentucky public school districts averaged $1,421 per student annually. The funds were intended to provide “critical academic support, address social, emotional and mental health needs, promote physical safety and sustain school operations,” according to the Kentucky Center for Economic Policy.

Somehow, Berea Independent failed to adjust its budget accordingly.

“When I was an interim superintendent in Danville, I let all of our principals and staff know when the ESSER funds dried up, the roles they created would also end,” he said. Thomas was interim superintendent in Danville during the 2023-2024 school year.

“If the ESSER funds created the role, then when the ESSER funds dry up, that role needs to go away,” Thomas told The Edge. “And I just don’t think that really happened here.”

The weakest ‘leg’

Under former District finance officer, Tony Tompkins, the District’s income projection for the 2024-2025 school year was 14.6 million dollars, and included the ESSER funds. The actual revenue without those funds is 12.2 million dollars, according to new finance director, Nathan Sweet, who informed the Board of his revision during the March meeting when Hatchett announced staff cuts.

Why Tompkins had factored ESSER funds into the budget remains an open question. The Edge was unable to reach Tompkins for comment.

In the interview, Thomas suggested that the “stool leg” without necessary facts was Tompkins, who announced his retirement shortly before the audit’s findings were presented to the Board.

“You know where we are financially, so that would probably have been all the information he needed,” Thomas said.

Moving forward

For next year’s budget, Sweet seeks to implement a tracking system.

“This all really ties back to the need to establish position control so that there is a centralized list of all positions, how they are funded, who is filling them, and how they tie back to the annual staffing allocations.”

Next up: What resulted from $400K in consulting fees?

A conversation with Dr. Ronald Chi, and reporting on a toxic culture at the District

If this was forwarded to you, the investigation is just getting started. To read the full accounting of what happened at Berea Independent, become a paid subscriber to The Edge.