Coyotes sightings on the rise now that it's breeding season

What dangers do these wild dogs pose?

There used to be a pair. The smaller coyote hasn’t come around for about six weeks now. I used to watch from my deck as they frolicked in the cow pasture behind my home. There was a pattern to their play: one would hunker down in the grass, hidden from view. The other, smaller one, would hop-run across the field, then stop. The hidden one would spring into the air and run to meet the other one. Then they would repeat this game.

Now, the larger of the pair skulks alone along the edges of the field. I know this because the recent snows have made its tracks plain.

Coyote encounter

My dog and I were out walking last week when she suddenly froze and looked ahead. There was the solo coyote, right in our path, merely feet ahead, watching us. The two canines regarded one another for a few seconds before the wild one turned and sauntered back into the woods.

The moment has stayed with me. I wonder: Will this happen again? What is the level of danger such an encounter poses? And also, what are the state and local policies regarding the coyote population in Kentucky?

Nuisance, not native

Coyotes are considered by Kentucky wildlife officials as a “naturalized” species, according to wildlife management and conservation expert, John Cox, PhD.

“They’re not native to Kentucky, but they’ve been here for decades,” Cox told me in an interview. Cox is an associate professor of wildlife and conservation biology at the University of Kentucky. He specializes in studying the wild, medium to large size mammals that live in the state, and has observed coyote behavior in the wild.

“Coyotes are partially filling the niche wolves did in the state about 150 years ago,” Cox said. “They are just incredibly flexible in their diet, and that’s what really has led to their success.”

They will eat berries, melons, birds, carrion, and other small mammals, including smaller pets, according to Cox.

For this reason primarily, the State considers coyotes a “nuisance”, Cox told me.

Indeed, the nuisance species page for the Kentucky Department of Fisheries and Wildlife Resources has a picture of a coyote upon it, with the warning that “…loss of natural habitat, residential or commercial developments, and some adaptations of wildlife in response to these changes can result in damage to agricultural crops or other property.”

And for that reason, said Cox, “You’re basically allowed to hunt them pretty much all the time. They’re considered to be year-round pests.”

‘Here to stay’

Kentucky was once famous for its plentiful black bear population, but by the turn of the last century, bears had been hunted and trapped out of existence in the state. “They used to export the pelts at the Big Sandy River,” Cox said. Black bears have since begun to return to Kentucky woodlands.

By the end of the Civil War, wolves and mountain lions were also extinct within Kentucky state lines, a situation that remains today.

The loss of these three large mammal predatory species meant bob cats and foxes essentially became the top of the woodland food chain, according to Cox. This gap in the order of things is one that coyotes have been filling ever since development in the US Plains and Western states began disrupting coyote habitat.

Coyotes have increased their range more than 40% since the 1950s, according to the National Geographic, which also reports that coyotes have been seen in all US states but Hawaii, and even as far south as the country of Panama. Cox said that coyote populations in Kentucky have especially taken hold since the mid-90s, and that any hopes of eradicating them are futile.

“They’re here to stay,” he said.

Curious, dangerous

Given that winter is coyote breeding season, I’ve recently witnessed a spike in social media warnings about not letting small children and pets go unattended, lest a coyote carry them off for supper.

Although it’s unnerving to see a Ring camera photo of Fluffy hanging limp from a coyote’s mouth, State officials strike me as slightly more sanguine, and seem to want folks to calm the hell down.

“It’s not a common thing to hear about a coyote just waiting to get somebody’s dog,” Lisa Jackson, spokesperson for the State’s Fisheries and Wildlife department told me in an interview. “It’s important to keep an eye out for them if you’re walking your dog, but you know that the human is the dominant predator, so you can scare them away. But, a lot of times, you don’t need to. Coyotes are just curious about you.”

My own experience corroborates this perspective. Still, when I walk the dog, especially at night, I have taken to always having a walking stick in hand, in case I need to use it to beat a coyote away.

It’s possible I will need to before the season is out, according to Jackson. “You might see them more often as they are trying to get the lay of the land, or if they’ve got pups they are trying to protect or feed. Then they might be keeping an eye on you so you or your dog won’t go near their den.”

So, coming too close just might bring out the mean dog in them?

“There are plenty of videos out there of coyotes harassing and even attacking bigger dogs, especially if they are traveling in numbers,” Cox told me. “They are quite territorial.”

Cox also told me that while it is rare for a coyote to attack a person, he still favors the advice to keep pets and small children from their path. “They can get a bit snappy, and there are the very rare instances where they’ve killed a little kid. When they hear an infant crying, it will definitely get the coyote’s attention because it sounds like a prey species in distress.”

Whether you have encountered a curious or a dangerous coyote is not something you can easily predict, according to Cox. However, his own observation is that the more rural a coyote is, the less aggressive it tends to be.

That’s because coyotes living in urban environments tend to be left alone by hunters, especially since city officials tend to frown on citizens discharging their firearms within city limits.

“The urban coyote populations have low mortality from people, so they develop much bolder behaviors than say a bunch of country coyotes,” Cox said.

Help on the farm

That’s not to say country coyotes aren’t full of tricks of their own. The pair I used to watch play in the field once entertained me by weaving themselves in and out of the herd of Angus that often is left to pasture there.

I half expected that the wild dogs would take down one of the smaller cattle. I had no frame of reference for what I did actually see: the larger coyote walked right underneath one of the grazing cow’s belly. The cow was unfazed. Actually, all the cows were unfazed. Not one reacted in alarm to the coyotes’ presence.

This dovetails with what Cox told me. Namely, that coyotes are good farm inhabitants, given that because of their flexible diet, they can clear a farm of voles, mice, and rats, even if they might also occasionally help themselves to the chickens.

A study published by Oregon State University also found that a pair of coyotes’ territorial nature can be put to good use, by sheep farmers in particular:

“If a pair of coyotes is not killing livestock, their dominance over the territory typically excludes sheep-killing predators and helps to prevent livestock losses … Thus, the territorial behavior by a breeding pair of ‘well-behaved’ coyotes is one of the best reasons for using non-lethal deterrents for predator management.”

The findings from this and other studies even led Benton County, Oregon officials to encourage local sheep farmers to let coyotes help “guard” their flocks. The rational is that because it is only older, bolder, desperate coyotes who kill sheep, letting coyote packs establish themselves in an area instead of chasing them off or killing them and disrupting their social order, will mean they keep each other in line and other predators out of their territory.

In other words, nice, intact coyote social orders lead to nice, untouched sheep flocks, or so goes the thinking in Oregon since 2019.

Coyotes also offer suburban neighborhood perks, especially if you’re a bird lover.

“Studies have found that where coyotes have been removed, the songbird densities and diversity goes down. It does so because without the coyotes, you have an explosion of all species the coyotes would suppress. Coyotes exert pressure on the next level of the food web — the smaller animals that bust up nests and eat eggs and chicks. Raccoons, skunks. Coyotes keep those guys honest.”

Best practices

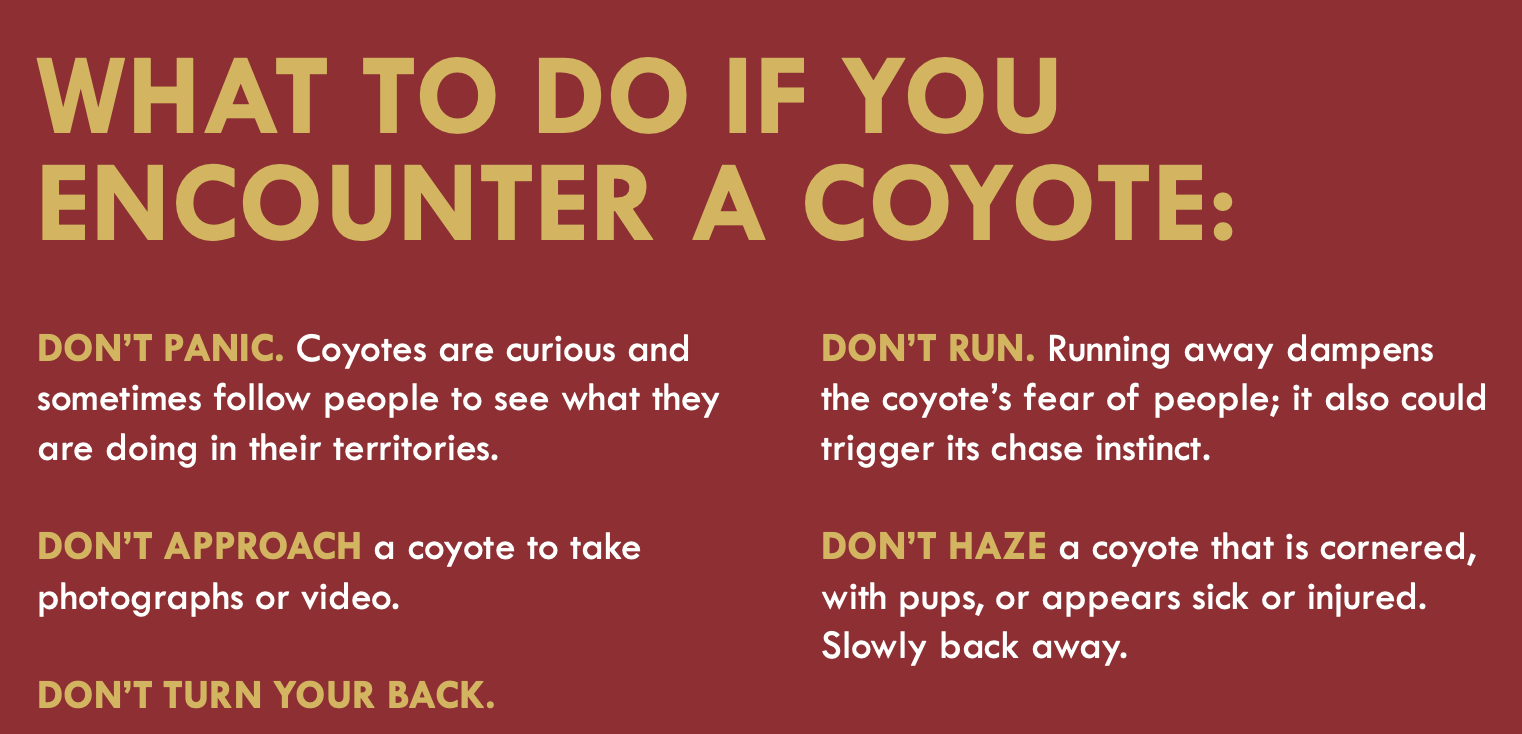

Kentucky wildlife management officials have put together a clear and succinct list of what to and not to do if you and a coyote should meet.

Here’s a preview, but if you visit their site, there’s more:

‘My’ coyotes

As for my coyotes, I am sad that the pair apparently has been destroyed. I miss witnessing their sheer joy as they played their version of hopscotch tag in the mornings as I sipped my coffee.

I realize not everyone feels that way. Still, as the Fisheries and Wildlife’s Jackson said, “Nature can be unpredictable, but it’s wonderful to observe.”

Most likely, a local farmer shot the smaller one, perhaps as it was raiding a chicken coop. It’s just a guess.

If Cox and the others are right, it won’t be long before another coyote moves into the area and takes the other one’s place. I will be glad to have him or her as my neighbor. And I will also carry my walking stick when I go out.

The Edge is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts right in your email box, become a free or paid subscriber.

Update: On January 22, 2024, the word “partially” was added, at the request of Dr. Cox, to the sentence, “Coyotes are partially filling the niche wolves did in the state about 150 years ago,” Cox said.